Ithacus was a 1966

study by Douglas, producers of the DC- series transport aircraft and

the Thor IRBM, for a sub-orbital troop transport.

The designer was Philip Bono, who reused elements of his

ROOST (Recoverable

One-stage Orbital Space Truck) and

ROMBUS (Reusable Orbital

Module-Booster & Utility Shuttle) studies from 1962 and 1964; these

were the first serious engineering proposals for reusable vertical

takeoff and vertical landing single-stage-to-orbit spacecraft.

This design family was based on an actively-cooled plug-nozzle engine,

a variable-geometry design with a movable blockage in the rocket

nozzle, which could change the shape of its exhaust to maintain

efficiency over a wide range of air pressures. Liquid hydrogen fuel

would be circulated through the plug to stop the latter from melting,

and this would also serve as an active heat shielding system during

re-entry. To lower the weight of things like skin and structure,

ROMBUS was to be huge, over 200 feet high (some sources say 95 but I

don't find this plausible), 78 feet across, with a fully-loaded weight

of over 6,000 tons and a payload capacity of 450 tons to LEO. (ROOST

was twice as heavy for the same capacity; ROMBUS got the weight down

by using jettisonable external hydrogen tanks rather than being fully

reusable.)

That was probably a reasonably workable idea, if very optimistic, but

the cost of building and testing such a huge vehicle would have been

far too high for NASA alone; so, perhaps inspired by USMC General

Wallace M. Greene who was proposing rapid-response forces, Bono

proposed an intercontinental troop carrier variant, the Ithacus, for

responding to "brush wars" before they got out of hand. This was

essentially the same engine and fuselage as ROMBUS, with the same 450

ton payload. It would carry a battalion of 1,200 soldiers ("Rocket

Commandoes"), plus equipment, on a sub-orbital flight path, thus

removing some of the need for American bases overseas and giving the

ability to respond to a crisis anywhere in the world in less than an

hour.

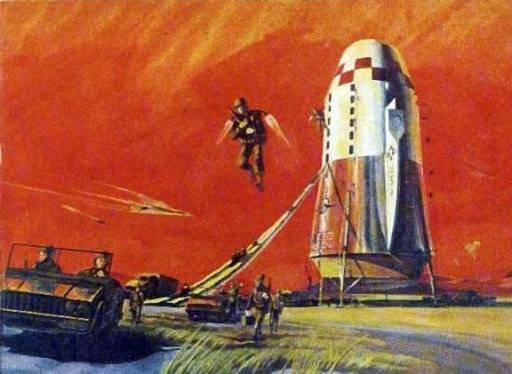

(The personal jet-pack appears to have been entirely a flight of fancy

on the part of the artist at NASA.)

Another version, the Ithacus Jr, would have carried 260 soldiers or

33.5 tons. These would be launched from an aircraft carrier, fuelled

by electrolysis driven by the carrier's nuclear power plants, and sent

in pairs: one full of troops, the other with all their equipment. (One

assumes this was to get US Navy buy-in for the project, but as the

illustration shows the carrier couldn't be used for much else until

after the hangar boxes had been removed.)

Recovery of the empty Ithacus would obviously present some

difficulties: if it were fully fuelled for a return flight, it would

need a proper launch facility in order for the massive thrust of its

main engines not to generate shockwaves and kick up huge amounts of

débris, damaging the vehicle as well as its surroundings. Reducing the

fuel load, so that it could take off with lower thrust and fly only a

few hundred miles at a time, was thought to be more practicable; then

it would be hauled aboard a Saturn-style crawler and moved onto a

cargo ship for return to the USA. But you'd still need to get liquid

hydrogen and oxygen into the recently-pacified trouble spot.

The tactical implications don't seem to have been studied in as much

detail. Consider: you are a Bad Guy by American standards. Your

military forces are causing trouble somewhere. You're probably more or

less aligned with the USSR. US reinforcements are on the way, coming

in nearly vertically, with a great big infra-red (landing thrust would

be a minimum of 10MN) and radar (from re-entry ionisation) trace; you

can't miss them, and they're not terribly agile. By 1966 the S-75

Dvina (SA-2 Guideline) surface-to-air missile, with its 200kg

warhead and 82,000 foot ceiling, has been in service for nearly ten

years: the North Vietnamese have them (as the USAF is finding to its

cost). Now I don't know just how damageable the plug-nozzle engine

would be, but this is certainly a thin-skinned aircraft, and if you

can knock it out at any sort of altitude all 1,200 troops are out of

action before they can fire a single bullet. You also score a huge

publicity coup: "They dropped soldiers on us from space, and we

still beat them!" So the Ithacus can't drop "anywhere in the

world" – it has to be somewhere out of any conceivable hostile SAM

cover, and then the troops have to go overland to where the fighting

is. (Even then, accidents are much less survivable than accidents to

aerodynamic transport aircraft.)

A payload allowance of 826lb per soldier, including their own body

weight, doesn't allow for anything in the way of heavy equipment: it's

about 20% more than the allowance for paratroopers aboard a C-130.

This is a very light infantry unit, with no tanks or even APCs (the

contemporaneous M113 weighs around 2,100lb per soldier, even without

the troops and their personal kit).

Also: what happens if they don't immediately win? It's like an

amphibious or parachute assault: you aren't going back the way you got

in, and you don't have much in the way of spare ammunition or food.

Only you don't really want to leave your hugely expensive assault

spacecraft lying around for the enemy to capture, so you'll probably

have to destroy it if things go badly…

So in how many situations do you have a non-SAM-covered landing zone

where 1,200 light troops can be reasonably sure of winning the fight?

Ithacus Jr suffers further because it reduces that to 260 troops with

even less equipment, and given the huge range of the thing, putting it

aboard an aircraft carrier just seems pointless: why send it in from

an ocean launch when you could send it in from the continental USA in

only a few minutes more?

There's also the concern that, well, the USA launching a great big

suborbital rocket towards a trouble spot just might be interpreted

as an ICBM.

This may be part of why the idea never went anywhere, though given

some of the things that did get built I suspect it was mostly the

cost. Bono went on to design the smaller

Pegasus VTOVL

(intended for very-high-speed transport and disaster relief, bearing

in mind this was also the age of Concorde and other SST development)

and SASSTO vehicles; none

of his designs was built, and he died three months before the first

flight of the loosely related DC-X.

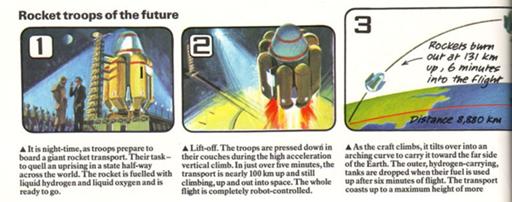

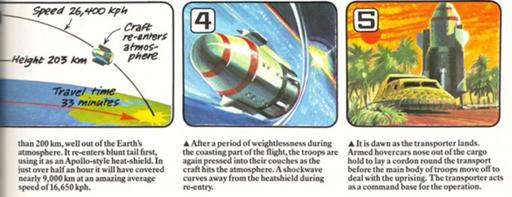

The complete failure of the project to get anywhere didn't stop it

from being included in The Usborne Book of the Future (1979), a huge

influence on the young RogerBW. These images are very clearly inspired

by the NASA art for Ithacus and Pegasus VTOVL.

One consideration that rarely gets mentioned is that a suborbital

transport like this is basically the same thing as a full space launch

vehicle: the speed through the atmosphere and delta-V demands are high

enough that you can't take significant short-cuts just because it's

not intended to achieve orbit. This isn't a simple up-and-down trip

like SpaceShipOne: you need nearly as much sideways speed as if you're

going all the way. (I suspect that heavy lift to orbit was always

Bono's real goal anyway.)

The idea of a suborbital troop transport was resurrected in 2002, with

the USMC's SUSTAIN (Small Unit Space Transport and Insertion) concept

(possibly to use the USAF's HOT EAGLE). This time, rather than

worrying about foreign bases, the idea was to avoid having to ask

countries for overflight rights; this seems largely to have been

spurred by a failed mission in November 2001 to try to find Osama bin

Laden, where the USA actually had to negotiate with Pakistan in

order to move its troops through Pakistani airspace. Imagine!

This is all very much on paper, but the scheme was for a two-stage

vehicle based loosely on SpaceShipOne (ahem, see above). This was to

carry 13 Marines plus their equipment, and land on a runway rather

than vertically. So you wouldn't have quite such a huge infra-red

plume, but to all the other problems you've now added the need for a

conflict where 13 Marines can make a difference (someone's been

watching too many action films), and where the enemy can't park a

truck across the runway. (Hey, why not have them parachute out?) The

only nominal point of this is that national airspace claims currently

end at 50 miles altitude, but does anyone in the US really expect a

foreign country to say "oh, you flew over us at 51 miles up, we're

just fine with that, rah rah Murica"? This got some talk in 2005-2006

but seems to have faded away since then.

But the concept art is really cool.

(I believe this is by Peter Bollinger, working for Popular Science.)

How could the idea be a useful one? Really you need something better

than conventional rockets, just as you do for a cheap surface-to-orbit

launcher. Use one of the nuclear engine designs, particularly one that

can heat air for thrust while in atmosphere, and the payload starts to

be a larger fraction of the overall vehicle mass. And as the fuel mass

goes down, you might get a certain amount of ability to manoevure as

well: something that can make a suborbital insertion to a few hundred

miles out from the trouble spot, then hedge-hop at supersonic speeds,

might have more of a chance. Keep it small, to put in a squad or two,

and frankly to be more expendable than a 1,200-soldier craft. It's

useful for embassy hostage rescues and similar small sudden missions.

Throttle down, air-drop the troops or land vertically, and fly away

again; you still have a limited range of conflicts in which it does

much good, and it's probably not worth the money to develop unless

you're also using it as a general-purpose space launcher, but at

least it can have some effect.

Comments on this post are now closed. If you have particular grounds for adding a late comment, comment on a more recent post quoting the URL of this one.