The mystery story when done well is an extreme form of the story

problem, which one can enjoy both on the level of normal fiction

with characters and plot and setting and so on and on the level of

working out whodunnit before the author reveals the solution.

I'm not a strict follower of the

van Dine or

Knox rules

(particularly as some of them were pretty clearly written as direct

criticisms to certain books by Agatha Christie). I'm more inclined to

favour the Detection Club approach, a compressed version of the Knox

rules, summarised thus by Simon Brett:

that the author pledges himself to play the game with the public and

with his fellow-authors. His detectives must detect by their wits,

without the help of accident or coincidence; he must not invent

impossible death-rays and poisons to produce solutions which no

living person could expect; he must write as good English as he can.

He must preserve inviolable secrecy concerning his fellow-members'

forthcoming plots and titles, and he must give any assistance in his

power to members who need advice on technical points.

But in any case, as with rules of grammar and perspective I think the

artist is better off knowing what they are, and perhaps breaking them

deliberately, than breaking them by accident. Van Dine in particular

is very impatient with the rest of the book, seeing descriptive or

character-analysing passages as mere wrapping round the meat of the

puzzle; I'm more prone to try to enjoy the book both as a puzzle and

as a story. (Apart from anything else, this means I can read it again

later even if I remember the plot.)

It's unfortunate when one can solve the mystery by the shape of the

story: when a key question is raised but never answered and nobody

ever chases it up, or when the detective mulls over the credentials of

the five suspects while the reader remembers that there were six of

them. This wouldn't necessarily be a problem for a new reader, but one

does start to notice these patterns after a bit, and it's a shame when

writers fall into them.

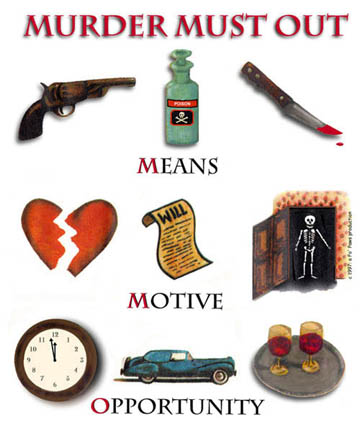

The puzzle part of the story is traditionally regarded as a triad of

means, motive and opportunity:

(T-shirt design from Fo'Paws Productions.)

Means were early gimmicks: the ice dagger or bullet that melts in the

victim, the undetectable poison, and so on. This sort of thing has

mostly faded away now, along with opportunity gimmicks like the

traditional locked-room mysteries (which I think it's fair to say that

John Dickson Carr examined so exhaustively as to leave little space

for innovation), and those puzzles that involve detailed reading of

railway timetables. (I seem to remember at least one Agatha Christie

short story that hinges on the complete impossibility of a train

running five minutes late.)

What's left is motive, and that's where the puzzle overlaps with the

good story: of these people, all of whom physically could have

dunnit (and probably all of whom have some sort of reason), which is

the one who actually did? At that point all those

character-analytical passages come into their own, and if the people

are well-enough drawn that will give clues that can be blended with

conventional means and opportunity information to come up with the

result.

As Dorothy Sayers put into the mouth of Harriet Vane, constructing a

detective story in Strong Poison: "She is a person with a

monomania—no, no—not a homicidal one. That's dull, and not really fair

to the reader." I regard it as a failure mode of a mystery story to

say "a loony did it for his own reasons which don't make sense to a

rational observer". Yes, clearly murderers are not thinking quite like

normal people, or we'd be up to our ears in corpses. But removing both

character and motivation (because the loony has to appear something

like a reasonable person, so most of what you learn about their

motivations has been faked) removes for me the enjoyable part of the

puzzle, and throws one back on exactly who was where when.

Comments on this post are now closed. If you have particular grounds for adding a late comment, comment on a more recent post quoting the URL of this one.