2008 non-fiction, an informal history of English science in the age of

Joseph Banks, William Herschel and Humphry Davy.

Well, it's more a set of interleaved biographies of those people

and of some others whose paths crossed theirs, with mention of their

science but always in a faintly terrified way; Holmes let

"spectography" get through the spell-checking process (twice in the

same paragraph), and is happy to talk of distances

so huge that they cannot be given in terms of conventional ‘length'

measurement at all, but either in terms of the distance covered by a

moving pulse of light in one year ('light years'), or else as a

purely mathematical expression based on parallax and now given

inelegantly as 'parsecs'.

No, Richard, they are merely distances, and a light year is simply a

larger unit than a mile, just as a mile is larger than an inch.

The primary goal seems to be to present these people as people, as

squabbling and obsessed and inconsiderate. (I am told that it's not

necessary for a biographer to think highly of their subject, though I

wonder why they bother if they don't.) There's no amateur psychiatry

or mention of autism here, which is something, though one can't help

but notice that reasonably wealthy men could get away with a lot more

simply because they didn't have to make people like them in order to

survive.

The other goal is to point out the degree to which the Romantic poets

(about whom Holmes has written several biographies) were involved in

the scientific life of the day, and vice versa; Davy wrote poetry,

Coleridge was invited to the Royal Institution to lecture on the

imagination. The resistance to science as "spoiling the mysteries of

nature" came rather later, and seems to have been driven more by

religious panic, since nonsense accreted to useful theology had

tainted the theology by association – so when the nonsense was

revealed, the theology was regarded as being under threat. (And one

can see the early retreats and secondary defensive lines: well, maybe

God doesn't do this thing that's now been explained, but obviously

he does that… oh, wait…)

A third strand deals with the construction of the scientific myth: a

great part of the idea of the lone genius who needs no assistance, and

of the single "Eureka" moment rather than the long slog, starts here.

Well, it works; but there's a lot of it, and I sometimes felt a sense

of stretching limited available material. Caroline Herschel's moving

out of her brother's house and into her own lodgings after his

marriage is mentioned twice, a few pages apart, each time as if it

were a new datum.

More interesting to me are the interfaces between the science,

engineering, and other things: and a reminder that the Montgolfiers'

ascents were done for the King of France, not a Revolutionary

Committee. (And another, almost accidental, assault on religion, since

it had been used to buttress the existing social order, and new things

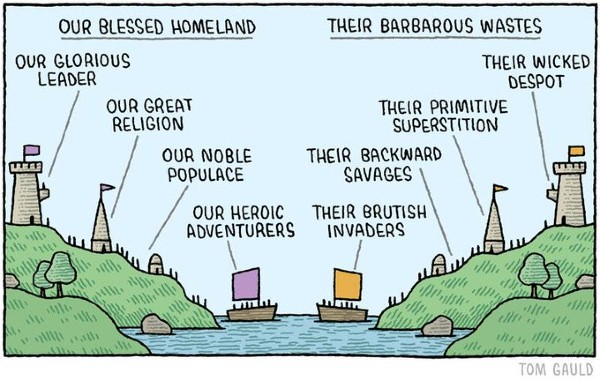

that could be done always upset that order.) The rivalry between

British and French science, exacerbated of course by the Napoleonic

wars, and the blatant deceptions used to make "our" science sound more

impressive than "theirs".

ObTomGauld:

(And, perhaps fortunately, a profound lack of the engineering skill

that might have created new and terrifying weapons.)

There's quite a bit on the balloon frenzy that followed the

Montgolfier ascents, until it suddenly evaporated as people realised

that controlling the direction of one's flight wasn't going to be

possible any time soon. (The later Falling Upwards, by abandoning a

chronological treatment, loses this sense of progression.) There's

plenty on how rapidly the Royal Society settled into complacency once

given a clear advantage, provoking the foundation of the British

Association for the Advancement of Science (no aristocratic patronage,

not happening in London) in direct reaction to it.

It may be unreasonable of me but I'm sorry to see here the same old

tales about Davy's lamp making mining safer; I read these in science

books for children in the 1970s, but even then they'd been known to be

false for over a hundred years. Deaths in the mines went up once the

lamps were brought in! Some of that was because seams that had

previously been considered too dangerous were opened again; some was

because the miners, forced to buy lamps just as they'd been forced to

buy candles from the company store, resented the expense and sneaked

in candles instead; some was because, the moment the gauze became

damaged, the flame-arresting property was lost. In fact, since what

everyone before Davy had been working on was ways of getting better

ventilation in the mines, one could make a good case that the lamp

made matters worse by delaying that necessary improvement. (And his

experiments with nitrous oxide, while undoubtedly great fun for

everyone involved, stopped just short of actual anæsthesia… and so

it remained for two generations, in part because of the fuss that had

been made about those experiments and the lack of visible benefit.)

But where Falling Upwards a few years later would be essentially

fun, this book is dispiriting, in its tales of discoveries almost

made and of opportunities lost. This may just be my present mood, of

course. The book's all right, but it doesn't bring on in me at least

the sense of enjoyment that that other volume did.

Comments on this post are now closed. If you have particular grounds for adding a late comment, comment on a more recent post quoting the URL of this one.