I've been playing with Flightgear again, now with a decent joystick

and rudder pedals.

(I got my hardware purchase in just before all joysticks and

pedals vanished from Amazon because of the new MS Flight Simulator

release, which is nice.)

Given that I'm running Linux, MS Flight Simulator isn't an option (and

given how much of the new version has to be rendered by remote

machines it's effectively spyware too, if only in terms of the general

area you're flying in, though I suppose most gamers are used to much

worse). X-Plane is still going and available for Linux, and I think I

technically still own a copy, but it's still commercial, and many of

the interesting aircraft are payware too. Flightgear is entirely free

and open source, and so are all its add-ons.

Flightgear aims for realism in its flight models first, prettiness

later, which suits me very well.

Here's an approach to Rayne Hall Farm airfield, near Braintree.

Not pretty. Nor is the modelling desperately precise; the airfield

isn't really on a little lump of ground like that, but the modeller

assumes that all airfields are flat.

Here is

what it actually looks like (looking from the other end, and with

snow).

On the other hand, the aircraft cockpit is an accurate 3d model of the

Cessna 337 I'm sim-flying, almost all of the switches work as they

should, the flight dynamics are pretty faithful, and – OK, note where

the plane is facing compared with the runway. That's not because I'm

incompetent. Down near the base of the propeller disc, directly above

the altimeter, you can see the windsock near this end of the runway.

At this point my aircraft is actually moving directly towards the

runway; the skewed angle is because I'm compensating for the

crosswind, and I'm going to touch the runway at that same angle and

have to put on a hard left rudder as the wheel contact changes my

direction. That's the sort of thing I care about more than how

accurate the airfield looks.

And that's the actual weather (not exact modelling but with the right

wind, cloud cover, etc.) that was happening there on the morning when

I was simming the flight.

FlightGear is also remarkably open and easy to interface with. I've

been writing code to read the scenery files for airports, navigational

aids, etc., and make them into overlays in the Viking GIS software, as

well as to talk directly to the simulator and track my progress. So

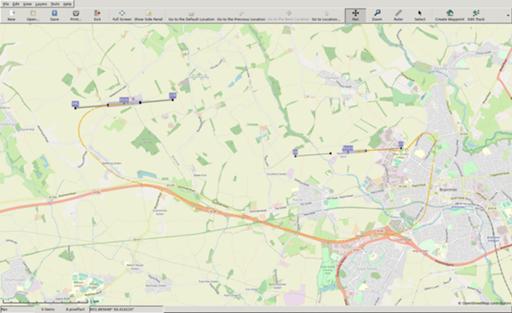

here's the track from that flight, overlaid with basic runway

information (details taken from the simulator's database rather than

OpenStreetMap that I'm using for orientation, so they don't quite

match):

I was able to pick up the A120 on my way out of Andrewsfield, the

previous airfield, then follow it by eye to the major road junction in

Braintree, turn north, and look around for the Rayne Farm strip.

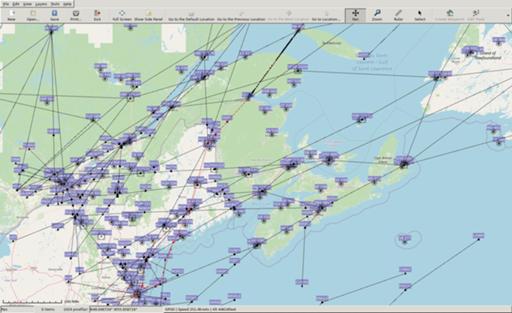

For something a bit more complex, here I'm about to start my descent

across New Brunswick in a Cessna Citation X (I prefer the light

business jets to the big airliners, because they can go to more

interesting airfields) on my way into Boston. Black lines are high

altitude airway routes, the labels are intersections and navigational

transmitters, and the red line is my planned route. The code which

generates my flightplan can dump it in Flightgear's native format for

use by its routeing engine as well as in something that Viking can

read.

This is a simulator, not a game – by which I don't mean to deprecate

either, but simply to say that any challenges are ones you set

yourself. There's no standard ladder of things to try; there's just

you, the aircraft, and the world. (Yes, all right, multi-player

flights are possible, but not on the big networks like VATSIM –

essentially because Flightgear is open and everything else that talks

to the VATSIM communications system is closed, so anything that would

work with both Flightgear and VATSIM would allow bad actors to inject

spurious data into VATSIM by means of a "fake" Flightgear.)

So my personal rules for keeping things interesting are:

- that I start at the nearest airport to where I live (which used to

be London City, but is now Wycombe Air Park) and expand my range

from there. I don't fly out of an airport until I've flown into it,

though not necessarily in the same aircraft or always starting from

the last place I landed.

- that I use current real time (though I'll allow myself some time

acceleration on long flights while I'm basically just waiting for

the autopilot to take me from waypoint to waypoint), and real

weather unless I'm deliberately making it worse.

- that as far as I can find out about them I obey real-world airspace

restrictions and procedures.

Comments on this post are now closed. If you have particular grounds for adding a late comment, comment on a more recent post quoting the URL of this one.